A minor miracle happens here every afternoon: a herd of goats materializes out of the sand. One by one they climb over the dune behind our huts nuzzling along our porches for any food left foolishly unguarded, or cling their way along the sandy slope above the shore browsing the fleshy, thorny brush that determinedly has taken hold there. They slowly make their way, singly, in pairs, and in little family groups along the edge of the cliff to their evening resting place at the top of the rocky outcrop that separates our cove from the larger, crescent bay of the village.

It is a visitation I have come to look forward to every evening as I swing in my hammock and catch my breath before walking up the sandy, griddle-hot path to dinner.

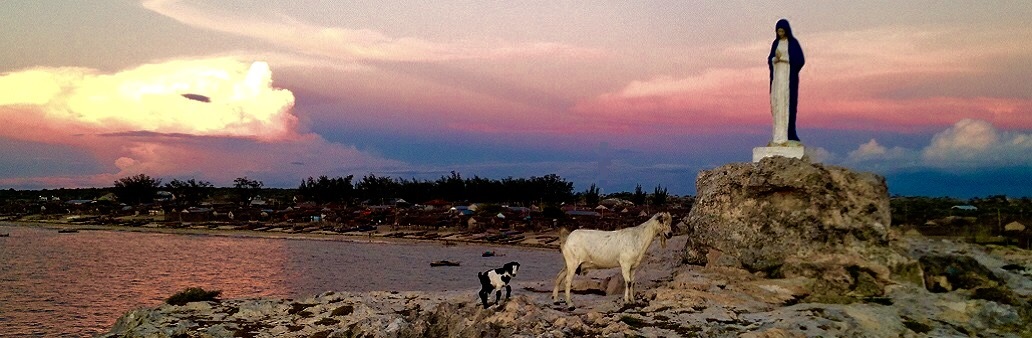

For some reason that no one has been able to explain adequately, there is a statue of the Virgin Mary at the top of the outcropping, hands held in prayer, head bowed toward the sea. As the sun sets on another glaringly bright and intensely hot day, the goats gather around and settle down under her calm gaze. No matter how early I get up, the goats are gone by morning. Even when I wake before sunrise to throw on my swimsuit and prepare my scuba gear by the light of my headlamp, they have already disappeared. You might see a few of them during the day, resting under a particularly tall bush, say, but you never see the entire herd. They seem to melt into the landscape with the coming of the new day’s heat, to reemerge only with its passing.

It’s a trick that I often wish I could conjure. Among the many challenges that this expedition is presenting is the heat. It never relents, even in the deepest night. Many of the Expeditioneers have abandoned their mattresses and mosquito nets and sleep out on their porches to catch whatever breeze may wander past on its way to somewhere else. It never lingers.

Each day emerges bright and still. Before I am fully awake, I can almost convince myself that I feel a bit of a chill and imagine the dim sky is actually cloud cover, but then the sun climbs a little closer to the horizon. The temperature jumps and the dawn light reveals the morning star shining in a sharp sky.

Some afternoons, the thunderstorms gather over the desert to the east. The light turns the rose-gold color of tempest. Lightning bolts strike the desert floor, and thunder marches toward us. The heat and humidity spike. Sweat stands in beads on arms and face and thighs, unable to evaporate. Flimsy curtains of slate-grey rain fall teasingly close, but never reach us.

Yet we are very lucky. The wells in our village still have water. The failure of the rains is causing many wells in the area to run dry and famine threatens. People are beginning to be on the move in search of water and food, and there is banditry about. I have never felt unsafe here, but when we travel to other villages, we go by truck rather than walk and are admonished not to stray into the bush alone.

On a journey inland last week, we finally met the rain and learned what it is like to live in that element also. We rose early and twenty four of us squeezed onto the floor of a tarp-covered, flat-bed camion to be tossed and tumbled through the desert, held in place only by the people on either side, catching glimpses of the sun rising behind the baobab trees standing sentinel against the fiery horizon.

The track ended at the shore of the Bay of Assassins, named for its treacherous tides and the use to which they were put by local pirates. We came to the Bay to learn about seaweed farming and sea cucumber harvesting and teach a little English. The journey would take us four days, travelling to ever-simpler villages, by ever-smaller pirogue, eventually hiking up our shorts and wading between villages at low tide.

As we jumped down from the camion, the clouds that gave the sunrise its passion protected us from the heat. We climbed into seven waiting pirogues to cross the Bay and were grateful that it would not be another blistering day. But the clouds had come alone, bringing no wind to fill the sails, and we were dependent on the paddles. Fifteen minutes from shore, the rain began. In thirty minutes, we were soaked through. In forty five, we were shivering. In sixty, our pirogue had lost sight of our companions. Their crews, older and stronger than ours, had far outstripped us. Our crew consisted of three boys, the oldest of which was not yet ten, the youngest probably five. Although their lean arms were roped with the sinew of men much older, the boys became weary battling the rain and waves, and our two men offered to take the paddles. Finally, we rounded a point and could see a low, dark village of sticks across the inlet. The other boats had long since pulled ashore. As we drew near, we saw no one: none of our group, no villagers. Everyone had taken refuge from the rain. Then a swirl of children came running, waving, laughing, announcing “Vazaha! Vazaha!” (“Stranger” in the local dialect) with a musical, high-pitched joy that I hope never to forget.

One by one the children took shelter, knees pulled to chests, in the sideways hull of a pirogue, looking for all the world like delighted peas in a pod. It was an image of such charm that it seemed impossible to be real. As soon as our pirogue touched sand, we hopped over the side, hoping to capture a photo, but the children, unaware of their perfection, couldn’t wait. Out they ran to us in the water, beaming and effusive in their curiosity.

They escorted us to the only masonry building in the village, a one-room structure with concrete floor and thatched roof that serves as church and school and community center. Here our companions were huddled around a table warming their hands on cups of rice tea as their dripping clothes flooded the floor. Dozens of adults encircled the outside of the building, staring in through the window openings with bemused faces, fascinated to watch us in our misery.

In the shallow inlets that surround the village, the conditions are right to cultivate seaweed. Just when we thought our clothes might have a chance to dry out, the tide had dropped enough for us to wade into the bay and stand thigh-deep in water as a bare-chested farmer instructed us in our afternoon’s work: how to clean the clumps of seaweed of parasites and algae. He spied a very beautiful young Bangladeshi member of our group and mused with averted eyes how, if he had a wife, he could be the largest seaweed farmer on the Bay….

After tending to the farmer’s fields of seaweed, we climbed back into pirogues to paddle through the mangroves to another village to help with the monthly sea cucumber harvest. The rain remained our companion, so we arrived soaked and shivering at that village also, but there was a large communal room where we could take off our wet clothes and rest a few hours on the foam mattresses that covered the floor.

We woke at midnight, squeezed back into our sticky, still-soaking clothes, and prepared to wade back out into the rain to harvest sea cucumbers at low tide. We were standing under the eaves, wondering whether our headlamps were waterproof, when word came through the village that the international company who buys the harvest had canceled the sale. There was lightning over the Bay, and it was too dangerous to be in the water. So with more relief than disappointment, we peeled out of our clothes and crawled back onto the mattresses in our underwear. We had been wet now for over twenty four hours; the desire to be dry outstripped any need for modesty.

Overnight the rain moved out to sea and we woke to clear skies. We watched as the refrigerated trucks of the international company drove away into bush. They had refused to stay another night and allow our village to harvest. There were other villages on other inlets to purchase from. Reasonable enough from the company’s point of view, but to our villagers, it meant another month would pass without income—a month in which disease could damage their crop or bandits could raid their pens.

Without the harvest, our usefulness was at an end. When the tide was right that afternoon, we piled into two large pirogues and crossed the dangerous mouth of the Bay with wind in our sails and sun on our faces.

When the camion drove back down the main street of Andavadoaka, I was amazed to see how much it had changed for me. The little village I left, the one that had seemed simple and wanting, had turned cosmopolitan in my absence. We passed women cooking street food, market stalls with dry goods, clothing displayed for sale on the fences. We passed a school, a church, a hospital, and of course Dados Bar and Disco, music still blaring. A few children called “Vazaha!” to us, it is true, but not with quite the same sense of wonder as had those little peas in a pod.

When the camion pulled up to our camp, it, too, had transformed: from a group of ramshackle huts to home. The rain had arrived before us and greeted us as we unloaded our gear. We watched from the cover of our porches as the setting sun turned the stormy sky into a concerto of color. Just then, the goats began emerging out of the dunes, and I joined their procession up to the outcropping to rest for a while in the rain at Mary’s feet, no longer needing an explanation, of why, exactly, she had been placed there.